The majority of the content and structure of this document is derived from work by Philip Colvin, the Chairman of the Crystal Palace Campaign. It was originally written for the charity GreenSpace as: ‘How to Run a Successful Community Campaign to Save Open Space’, 2004. We are very grateful to Mr Colvin for allowing the LFGN to reuse and provide this copy of his work. It includes updates (of such things such as the localism act) curtesy of London Parks & Green Spaces Forum.

Page number

1 Getting going 2

Start early 2

Top tips 2

Working with the local authority 2-3

Parks and Green Spaces Strategy 3

2 Starting your campaign 4

Public meetings 4

The First Meeting 4

Running the meeting 4

Tips for running a good meeting 5

3 Developing a campaign 6

Working with other groups 6

Keeping focused 6

The team 6

Running the campaign 7

4 Expanding your campaign 8

The committee 8

The role of the spokespeople 8

Building up the campaign 9

Why is your park/green space important? 9

Surveys 9

Newsletters 9-10

Creating a website and social media 10

Direct action 10

Petitions

Lobbying 12

MPs 12

Councillors 12

Celebrities 12

The developer 13

Logistics 13

Finances 13

Insurance 13

5 The planning system 14

Policy involvement 14 1.

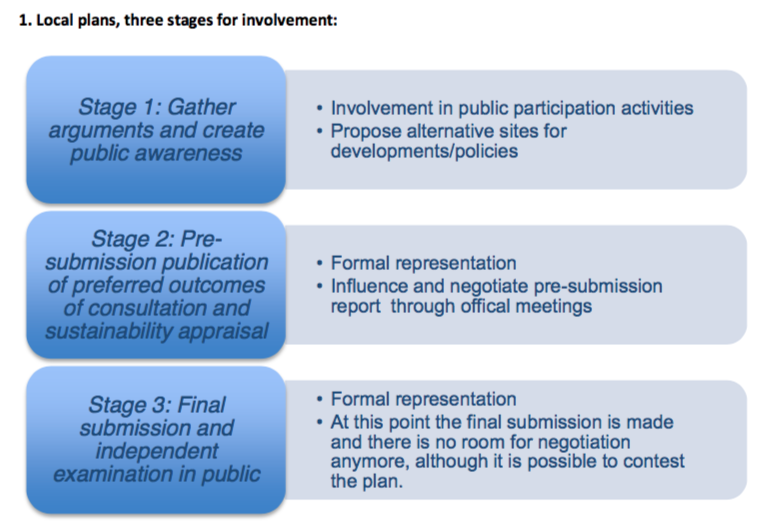

Local plans, three stages for involvement 14

2. Neighbourhood planning, three ways 15 3.

Designate local green space 15

15-16

16-17 Table 5.1

Statutory bodies 18

Table 5.2

Material considerations 18

Table 5.3

Relevant London Plan policies 19

Other 19

Village Green 19

Register of Historic Parks and Gardens 20

Alternative relevant documents 20

6 Useful links 21

Outside policy area

How to support involvement?

Organisations

Examples of campaign websites

Examples of petitions 24

Page1of24

11-12

21-23 23-24

1 Getting going

Start Early

If you want to save your open space, start now, before it is threatened. Go around your neighbourhood with your friends and identify sites which might be under threat: the tired, sad, neglected open space or the fringe of the park that is used to store skips in, the bit of woodland at the back of your estate, the triangle behind the railway track where your kids play, or where nature has taken over. Then set about protecting it. Make the site look valued and reclaim it for the whole community. It is much harder for a local authority or developer to choose a site which is loved, used and designated than one which is underused and forgotten.

Top tips

- Form a friends group, or even a management group, to protect and maintain the land.

- Show you love your local green spaces! Clean them up and plant flowers.

- Hold community events on your green space.

- Connect with other groups active in the area who are campaigning on seemingly different causes.

- Include people from all walks of life and across the community: an inclusive campaign is much more likelyto be successful.

- Try to engage people with the site, such as through gardening, tree planting, play groups or othercommunity activities.

- Think about the connections between protecting your green space and other important things for thelocal community such as school provision, health and equal access to green space for all communities. Remember that often the people who need the park most are more vulnerable groups, who also might find it more difficult to campaign. So try to make your campaign include them and stand for their interests.

- Give the campaign and spaces you want to protect a name and display the name prominently on a welcome board, with contact details for people to connect with the campaign.

- Use the planning system. See Chapter 5.

- Work with the local authority to consult with the public over the future of the park, or run a consultationexercise yourself, using it to develop regeneration proposals for further consultation.

- Ask to see any plans or strategies the local authority has for green spaces.

Working with the local authority

Working with local authorities can be bureaucratic, but there are many benefits to being involved in public consultations and planning processes. Also, if there are any disagreements between your campaign and the local authority, demonstrating that you have engaged proactively in their processes can be very helpful in getting them onside.

Putting up your own proposals will avoid charges of “nimbyism” (Not In My Back Yard). These proposals might include regeneration of the parkland itself. But if the local authority proposal is for something of social worth like a school or a hospital, you could go further, and try to find a compromise solution which involves building the scheme elsewhere. If you declare yourself “anti-school”, you will have lost before you even start. Try to avoid the debate being “green space or school” but “where shall we put the school?” Make sure to take into account as early as possible the needs and priorities of different groups in the community.

If you do find yourself in conflict with the local authority, it is worth trying to continue to solve the problem with reasoned debate, compromise and dialogue. A local authority is composed of officers and councillors from many different parties, with many different views and motives. Through patient argument it can be possible to persuade them one by one. Simple things such as asking about the development, finding out what the local authority wants to achieve, what their motives and justifications are and so on can be a good starting point. In many cases, patience and perseverance can result in productive dialogue being reached.

Parks and Green Spaces Strategy

A Parks and Green Space Strategy is a document which sets out a local authority’s vision for its parks and green spaces. This will include the goals it wants to achieve over a period of time (usually 5 – 10 years), and allows it to find out about the needs of its communities and determine what it wants from its parks and green spaces. It allows the local authority to develop a strategic approach to the management of its green spaces.

If a green space is identified in the strategy as being of great value and importance to the community, it will be much more difficult for planning permission to be granted on the site. As part of developing strategies, local authorities should undertake assessments of all of their park stock. These audits will allow it to identify parks and green spaces according to their value to the community and the level of use.

If you want your local green space to be recognised within the strategy as being a site of high value, then you should make sure you feed this into the consultation stage. This is a chance to influence the strategic management of green spaces in the area and make sure parks are not seen as limited value by the local authority.

Find out if the local authority has a Parks and Green Space Strategy in operation by contacting your parks department. If it has, read this thoroughly and make sure it is honouring the commitments it has made. If it does not have one, perhaps suggest to the local authority that you would like to see one developed, and you would be keen to be consulted on it.

Some local authorities are replacing their parks and green spaces strategies with green infrastructure strategies.

‘Consultation Starts Here’

From the Crystal Palace Campaign, Philip Kolvin:

“The Crystal Palace Campaign consulted 40,000 households and local primary and secondary schools over the future of the Park. We produced the results in our book ‘Consultation Starts Here’ and got Mayor Ken Livingstone to write the foreword. Once the cinema development was defeated, we built on the results by calling a meeting of 80 local groups and statutory agencies to plan the future of the Park. To ensure equality amongst participants we decided not to run the meeting but to hire in an independent facilitator. The process continued, funded by the London Development Agency, community groups and our former adversaries Bromley Council.”

2 Starting your campaign

Public meetings

The First Meeting:

The best way to kick off a campaign is to get together with others in the community and plan a public meeting. This will achieve lots of things:

- Test local opinion. Do people feel as strongly as you?

- Define the aims of the campaign. Gather together potential workers and supporters.

- Raise awareness and create publicity.

- Raise finance. A bucket is the campaigner’s best friend.

- Register your presence.

- Connect with other groups.

- Start to influence decision makers.

Running the meeting:

- Choose an accessible venue and time. Try to avoid clashing with other local or national events and try to avoid times when people have family, work or religious commitments.

- Check the logistics of the venue before the meeting. Choose a venue which is inclusive to all communities in the area.

- Appoint a chair, maybe a respected and supportive local figure.

- Pick speakers. A local expert will lend weight to the proceedings. An elected politician will tell local peoplethis is being taken seriously. An ordinary local person will underline that campaigning is by people, forpeople.

- Decide on the agenda. Copy the agenda, for placing on chairs.

- Publicise the meeting. This can be done by several methods, including: posters in shop and housewindows; leaflets door to door around the park; hand-outs at the station; put posters on trees in the park with a big red ‘X’ and the word “CONDEMNED”, followed by details of the meeting. Sometimes the local press will advertise the meeting for free.

- Put the name of your campaign prominently in front of the speakers’ table and on the wall behind it.

- Arrange a photographer.

- Appoint a record-keeper or minute-taker

‘Snowmen and snowballs’

- From Crystal Palace Chairman, Philip Kolvin:

“At an early stage, planning permission was granted for the multiplex development on our park. We realised that unless we could stop the permission in its tracks, the building would be thrown up and our campaign would be over before it had begun. So we called a public meeting. I explained how dire the situation was and that we needed £25,000 within 5 days to start a legal challenge to the planning permission. An old lady came up and said “I believe in what you’re doing”, and gave me a cheque for £1,500. We had our money in 50 minutes. Later, we held huge public meetings where we pitted election candidates one against the other. It was amazing to have ministers, MPs and councillors making promises to us about our park. Crowds turned up to see them. We had to put a tannoy in the car park. The press loved it. It must have depressed the developer no end. At one meeting, we took a vote: the development lost 1,250-nil. Point made.

It is crucial to use the energy from a public meeting to drive the next event. A snowman is made and admired, then melts. A snowball rolls, moves and grows. We would call the meeting, at which we would secure the commitment of the community to a direct action event, which the press would then advertise for us. After holding the event, we would carry lots of pictures in our next newsletter, which we would use to publicise the next public meeting, and so on.”

Tips for running a good meeting

A well-run meeting will increase your credibility and support for your campaign. Start on time and try not over- run.

- Announce the purpose of the meeting.

- Describe the agenda and provide printed copies.

- State what time the meeting will terminate, and stick to it.

- The main job of the chair is to keep the meeting focused and contributions to the point, and to preventpersonal attacks.

- Respect everyone’s opinion and try to resolve any disputes by negotiation.

- Be honest about bad news and involve all members in the solution.

- Make sure everyone signs an attendance list with their address, phone and email. This will enable you tostart creating a database which will also allow you to send a written follow-up to keep people informed ofdevelopments.

- Know what you want to achieve. This can include, for example: a resolution to form the campaign; an agreement as to its core aims; a vote against the development; an agreement on the next step for the campaign; a positive step which everyone can take, whether writing a letter or becoming closely involved in the campaign.

- Conclude the meeting with a summary of what has been agreed and decided and thanks again to all attending.

3 Developing a campaign

Working with other groups

Taking on a campaign can be a daunting prospect. However once you are able to get the word out many members of the community are likely to come together in aid of your cause. It is also likely that there are existing community groups in your area working with other areas of green space. It can be greatly beneficial to contact these groups as they probably have a wealth of information they can share.

Working with others can also provide ideal opportunities to recruit new members, publicise activities and exchange ideas. They may also know of useful local suppliers, which local politicians are supportive, which organisations can help, and local or national sources of grant aid. Participation in wider networks is a useful way to tap into a pool of information, expert knowledge and shared resources. The best way to find out about such forums is to contact your local authority, your citizen’s advice bureau or your local library.

Try to reach out beyond your immediate groups and networks to get more people involved. This can be a great way of bringing the community together and running a more successful campaign.

Keeping Focused

The business of campaigning is to:

- Direct your efforts to the result you want and to nothing else.

- Lever in all the help and support you can.

- Maximise the output from your resources.

There is only so much human effort that can go into campaigning. The key is to make sure none of it is wasted. So be clear about what your targets are!

Directing your energy involves prioritising. It is likely that all sorts of ideas will arise. You can’t pursue all of them. Decide what you can do well, what will have maximum effect, and go for it.

The Team

At the nucleus of a large campaign could be:

- Chair and vice chair

- Treasurer

- Secretary

- Press secretary

- Newsletter editor

- Newsletter distribution director

- Supporter liaison

- Web-site editor

- Social media editor

- Events organiser

People taking on these roles can be referred to as ‘the Committee’, or ‘the officers’. Smaller campaign groups may not need so many formal roles.

Running the campaign

Meetings can be more productive when there is a clear purpose and structure. For example, decide who is coordinating each meeting, and the wider role of the chair, the committee, and the general meetings. What decisions may be made day by day outside the committee, and by whom?

Planning ahead can help, with ongoing small events which are easy to organise and keep the campaign ticking, and large events which aren’t so frequent that they sap energy.

You can achieve a huge amount by empowering other people and encouraging initiative. The general public needs to know clearly what they can do to support your campaign. Build links with schools, religious groups, residents and amenity societies, ecological groups, youth clubs, sports groups, walking and cycling forums, etc. Create web-links to their sites, and vice-versa. Social media and emails can enable day to day decisions to be taken with minimum fuss or disruption.

Remember to celebrate results and hold social events. Affirmation of volunteers is extremely important. Keep your supporters informed.

4 Expanding your campaign

The committee

The committee is there to channel the community’s energy to win the issue, but it can help to involve new people as the campaign continues. Committee meetings should usually be open to all supporters, to encourage greater involvement and initiative. In addition, open general or public meetings should be organised to invite as wide a group of supporters as possible to join the campaign.

The role of the spokespeople

Campaign spokespeople have special and difficult roles, for which their previous life may not have equipped them. They usually include the Chair, Secretary and Press Spokesperson, who must:

- Be the public face of the campaign at public meetings and demonstrations.

- Represent the campaign with politicians and the opposition.

- Help steer the thinking of the campaign, making key decisions if that is their agreed role.

- Mediate differences in view among the committee.

- Inspire and motivate others.

- Include diverse opinions and groups.

- Lead by example, with humility, humour and respect.

- Accept responsibility for errors if necessary!

-

‘Our great strength’

From the Crystal Palace Campaign, Philip Kolvin:

“We were a rag tag and bob tail group which grew to massive proportions really quickly without ever developing a proper underlying structure. While this caused no end of organisational and political difficulties it was also our great strength. We had no membership, so you could drop in and give whatever support you wanted when you wanted. If you waved a banner, you were a member. We had no constitution, so we could be what we wanted to be, and change when necessary. This prevented our opponents ever getting a real handle on us. When we were asked how many members we had, we joked that we didn’t have a clue. Maybe the dozen committee members sitting round the kitchen table, or the 2,000 registered financial supporters, or the 40,000 who signed our petition. Who’s counting?!

“The Campaign” came to be seen by the public, press and politicians as a powerful organisation. In truth we were a small handful of people who became adept at levering in community support for our ideas and, by listening carefully, effectively representing the predominant community view. After the multiplex cinema scheme was abandoned, our fluidity meant that we could start to campaign for positive change immediately, with no procedural impediments. We had no elections, which outraged some, but meant that we grew into our roles and came to be seen as the face of the Campaign. But we also went where the energy was. We accepted help from hundreds of talented people, channelling their contributions to what we needed most. We piggy-backed on the reputation of national groups like Friends of the Earth. https://www.foe.co.uk/ . We formed close alliances with other local organisations, forming a group of groups to co- ordinate our campaigning activities. We worked jointly on lots of ventures, particularly legal actions and planning battles. And, finally, we built the biggest alliance of all, with our erstwhile opponents Bromley Council, in planning the future of our Park together. You can’t plan Governments or businesses with such loose structures. But, even now, I still believe that grassroots activism thrives in such rocky soil, using creative friction and individual energy as its catalyst. Provided those at the heart of the campaign are identifiable and trusted, you do not need to fossilize your campaign in constitutional niceties.”

Building up the campaign

You can only survive so long on slogans. You need to build up a convincing case, which you can deploy when necessary.

Why is your park/green space important?

(See also Chapter 5 on Planning Policy)

You could consider questions such as:

- Is there a deficiency of open space in the area?

- Is the residential population large, or dense, or poor?

- What is the ecological value of the park/green place?

- What is its historic value?

- What is its cultural value in the life of the community?

- What is its recreational value?

- How far is the nearest alternative?

- What vulnerable communities does it serve?

- Does it enhance community integration?

- Does it help secure equal access to green space across the community?

- How many busy roads does one need to cross to get there?

- Does it serve the same age-groups or recreational needs anyway?

- How many people use the park/green space? How do they use it?

Surveys

Remember to survey on all sides of the park/green space, and include children and diverse communities.

You could consider questions such as:

- What proportions of local people want to see the park/green space remain a park?

- What do they think of the development?

- Is it unfair on certain groups? Is it inequitable?

- Who will have access?

- What alternative ideas do they have?

- What is wrong with the proposed development? It does not belong in a park/green space, but what are the other arguments?

- Is the development too big, too ugly, the wrong use, the wrong location, or would it have adverse recreational or ecological effects, or cause traffic problems, or air pollution? What is the need for the proposed development? Why would it go better elsewhere?

If the park/green space obviously needs some tender loving care, it is better if you can suggest a viable alternative. If the local authority won’t carry out public consultation as to its future, or bring local groups together, you could do so.

Get all of your arguments into the public domain, through newsletters, websites and public meetings, and use them whenever you are interviewed.

Newsletters

One of the best ways to reach, inform and energise the community is to publish a regular newsletter.

The purposes of a newsletter are to:

- Inform people of your campaign.

- Raise your profile.

- Set out the facts and arguments.

- Publicise your next event or meeting.

- Tell people what they can do to help.

Tips for designing newsletters:

- Pick a logo for your campaign and stick to it.

- Use a big headline on the front page.

- Include lots of graphics and photos.

- Keep sentences short.

- Summarise the big points in text boxes.

- Get quotes from local people: “Why I support the campaign”.

- Check facts, spelling and grammar. Look professional: it generates support and frightens the developer.

- Show contact details – phone, web, email and address.

For examples, see this website for the Save Hervey Road Sports Field campaign

Creating a Website and Social media

You should think carefully whether a website would be appropriate and useful for your group as it can be a time consuming project. Firstly, you must buy a domain name for your group (for example www.crystal.dircon.co.uk – this is the address people will type into their computer to find your website) which will cost approximately £20 a year. Secondly, you must pay for a company to host or ‘hold’ your website on the internet so that people can find it when they type in your domain name. Prices for this service start at around £40 for a year.

There are lots of tips online for building simple websites. As a rule of thumb, keep content as concise as possible, with the key information prominently displayed.

You can use your website to:

- Publicise events and activities.

- Describe what your campaign is about.

- Create links to like-minded organisations.

- Ask for help.

- Tell people what they can do for you.

Try to engage people through a Facebook group or twitter. If you have anyone in your campaign who can produce short videos, they can be a great way to get attention for the campaign.

Direct action

Direct action has lots of benefits:

- It raises consciousness.

- It demonstrates support for your campaign.

- It generates press attention.

- It tells the world you mean it and you aren’t going away.

- It gives your supporters a chance to meet their fellow supporters.

- It can slow up or halt the progress of the development threat

- But it also exposes you to huge risks.

But it can also be risky:

- Maybe no-one will turn up.

- The day might go wrong. The police might try to break you up.

- If you strike too strident a note, you might alienate moderate supporters

‘A snowdrop for next spring’

From the Crystal Palace Campaign, Philip Kolvin:

We started with small events. At a picnic in the park I planted a single snowdrop to demonstrate that the park would still be a park next spring. It was. As we grew in confidence we got big. We held a march from the Park to the Empire Leicester Square, the flagship of the proposed multiplex cinema operator UCI. A thousand people came dressed as film characters. We called it Strike Back Against the Empire. Darth Vader handed a petition of 40,000 names to the manager. A spin-off group, Boycott UCI, started to picket outside the Empire regularly, diverting customers to other cinemas who were not going to destroy our precious park. Eventually, we had the confidence to hold a national day of action, when we picketed all 40 UCI cinemas in the UK from Strathclyde to Poole, working with Friends of the Earth groups in many places. The pressure we put on UCI was a key element in getting the scheme to collapse. We felt a bit sorry for UCI at first. They had not known the extent of local opposition when they first got involved. But we had to make an example of UCI so as to deter further operators from signing up, so we fired all of our direct action arrows at this single target, which proved to be the Achilles heel of the scheme.

Our slogan was “Militant but lawful” in order not to alienate local or institutional support, and to avoid legal action. This was tested when a group of eco-warriors occupied the site, bringing high press profile to the site but arousing mixed opinions locally. That created a dilemma for the Campaign, which was heightened when the local authority sued an 82 year old local lady for bringing the eco-warriors a bread pudding while intimating to us that we would be in the firing line unless we publicly denounced the eco-warriors. We published a newsletter in which we published the implied threat (thus humiliating the local authority still further), declared our own commitment to solely lawful action, but refused either to support or denounce the means used by the eco-warriors to protect the site, since they were nothing to do with us. Instead, we set out the arguments for and against their civil disobedience and left the readers to make up their own minds. In the end, it cost the local authority over £2m to evict the eco-warriors. So we felt that we were right not to lend public support to their illegal occupation, however much we admired their individual courage.

If a community group behaves unlawfully, or incites or gives practical support to unlawful action, it risks legal proceedings for damages or an injunction, which most insurance policies will not cover.

Petitions

Petitions can be a powerful tool if used well.

Top tips for petitions:

- Make it clear what the problem is

- State briefly what you are asking for

- Get out there. Organise the team to hit the streets, the workplace, the schools, community centres,religious organisations, cafes and pubs etc.

- Put the petition on your website.

- Put it in your newsletter, to get others to collect signatures on your behalf.

- Have the petition available at your meetings and events, to collect signatures and distribute forms to thosewilling to do so.

- Get local newsagents to leave petition forms on their counter.

Make sure there are room for signatories’ address and email address, and a box for them to tick giving you permission to contact them. Otherwise, you are in danger of breaching the Data Protection Act.

When the time comes to deliver the petition, deliver a copy. Keep back the original and make it grow. Use the names and addresses you collect to create an e-newsletter. This reaches thousands of interested people at nil cost.

In some cases a ‘Pledge’ can be more useful than a Petition as it identifies more committed supporters who may be prepared to help out or take action, e.g. ‘We the undersigned pledge to save our green space by taking any action necessary, including occupation of the site if necessary’.

Lobbying

Members of Parliament, councillors and celebrities who agree to back you can be of great benefit to a campaign, particularly when facing re-election.

Tips for dealing with politicians:

- Try to remain friends with them.

- Keep in regular touch with your political representatives, but keep your communications brief and to the point. You might ask your supporters to write to their MP, supplying the text if necessary.

MPs

MPs might be persuaded to:

- Speak at a public meeting.

- Give you a quote for use in your literature.

- Propose an early day motion in Parliament.

- Refer to the issue in a Parliamentary or Select Committee debate.

- Write to other politicians or political bodies on your behalf.

Councillors

Councillors are usually in a position to exercise more direct control. They might:

- Try to get funding for regeneration or maintenance of the park.

- Influence policies in the local plan.

- Vote or speak on planning applications.

- Work to change hearts and minds in the local authority, whether formally or informally.

Celebrities

Celebrities might:

- Give you a quote for a press release.

- Allow themselves to be photographed on site.

- Take part in some direct action.

- Make a speech.

- Be your patron.

-

‘Getting noticed in Europe’

From the Crystal Palace Campaign, Philip Kolvin:

We were lucky to have strong support from politicians. Our local MP regularly turned up to public meetings, and wrote letters to the local authority and other bodies on our behalf. Another MP even presented a Parliamentary bill which we drafted to transfer ownership of the park to the London Mayor! We got local councillors to chair our meetings, which built their standing and our profile.

Our MEP was key in getting us noticed at European level, both by the European Commission and the European Parliament. Our Greater London Authority Members took a deep interest at regional level.

The Developer

The developer has money, expertise, contacts, and the time. They only need to win once, whereas you need to protect the park for ever.

The campaign, though, can leap past obstacles easier than the developer. Sometimes it’s necessary to second guess the developer, and make sure the campaign stays one step ahead of the development plans. Their motivations are not the same as the campaigns. Starting early can help here! The campaign can be more flexible than developers, using many different angles and avenues as outlined on this webpage

Logistics:

Finances

A successful campaign needs finance – not millions, but enough for its core activities, and to respond quickly in times of emergency.

It is always easier to fund-raise for a specific event, or to deal with a particular crisis. People are quicker to support a particular goal than a general aim. Look online for good tips about fundraising

Here are some links to start out:

http://www.dsc.org.uk/Training/DSCFundraisingTraining/FundraisingTips#.VWxC0NJFCM8

http://www.cafod.org.uk/Fundraise/Guide-to-fundraising/Top-ten-fundraising-tips http://www.justgiving.com/en/fundraising/fundraising-ideas

And keeping costs down can be just as important as fund-raising. You could aim to get some professional help for free. Businesses may offer benefits in kind, like photocopying, catering, transportation or sound equipment.

Insurance

If your group carries out any practical work on site, or if you plan to organise events in the park, you should have insurance to cover your activities. You will need public liability insurance to cover accidents to the public and personal accident insurance to cover accidents to volunteers working on the site. If necessary, get professional advice on this, start by asking for advice from organisations such as the Citizen’s Advice Bureau, The Conservation Volunteers, nearby Friends of Parks Groups, etc.

5 The planning system

In case of a threat to your local green space it is important to know how you as a local resident or other interested body can help to protect this place. Bearing in mind recent planning reforms related to the Localism agenda, there are more opportunities for groups to influence local governance and thereby protect green spaces. On the following pages we show you how to act; at which points of a development you are likely to intervene successfully (ways of involvement) and who to talk to (how to go about this involvement).

Policy involvement

Within the boundaries of planning policy there are several stages at which you can influence the plans designed for your local area. Throughout the writing process of local plans for example, residents are invited to contribute their content whilst neighbourhood plans and local green space documents require you, local residents, to write your own policy document. These different policies give you the opportunity to exert influence and create new policies to protect your local green space, an overview of which will be presented below.

Figure 5.1 – Stages of involvement in the local plan

London Boroughs are responsible for preparing Local Plans and it is important to first read your Borough’s ’Local Development Scheme’ and ’Statement of Community Involvement’ to find out what policies are already in place and how they plan to involve you. In case you think these do not provide a robust framework to protect green space you can propose alternative policies that are to be included in the local plan. Additionally, this is the time (if you have not done this before) to increase awareness of your case and gain support. During stages two and three you can participate in formal participation events and raise your concerns about certain developments.

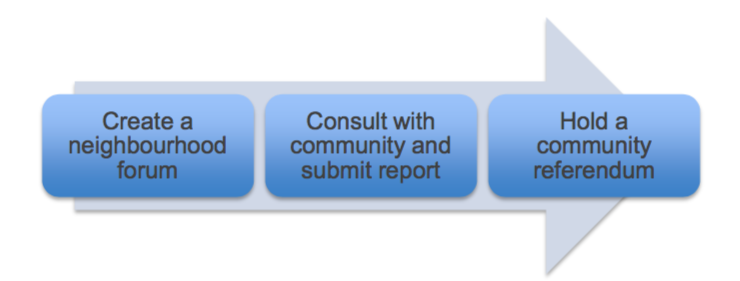

2. Neighbourhood planning, three ways:

Neighbourhood planning was introduced by the previous coalition government and was intended to give local communities more power in certain circumstances when it comes to planning. It would generally have to conform to Council ‘Local Plan’ policies, and be accepted by the Council following a lengthy process. Neighbourhood planning requires a community to create a neighbourhood forum, who can draw up a plan together. It is important to remember that this planning policy can be effective if it is to fill a policy gap; if it is merely an addition to an already existing policy it is questionable whether the lengthy process (about 18 months-2 years to develop) is worth the trouble. Similarly, if immediate action is necessary then neighbourhood planning might not be the best way to protect green space. However in the longer term it might be a relevant strategy. Under the header of ‘neighbourhood planning’ there are three different ways to get involved:

- Neighbourhood plans consist of ‘general planning policies for the development and use of land in a neighbourhood.’ (DPCL)

- Neighbourhood orders ‘permit the development [communities] want to see – in full or in outline – without the need for planning applications.’ (DPCL)

- Community Right-to-Build orders ‘allows certain community organisations to bring forward smaller-scale development on a specific site, without the need for planning permission. This gives communities the freedom to develop, for instance, small-scale housing and other facilities that they want.’ (DPCL)

To use any of these powers, a community should:

3. Designate local green space

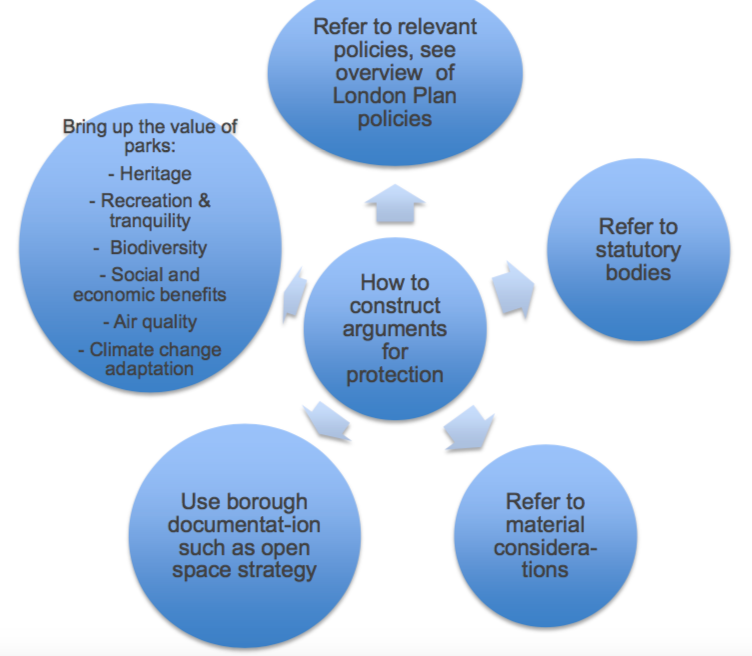

A local community needs to prove and/or clearly show the value of the green space to have it designated and protected as a local green space. This is done through the submission of a written statement in which it is important to refer to the policies and documents of statutory bodies to support your claims (see tables 5.1 and 5.3). Also the valuable functions of green spaces that you could use in such a statement are discussed in figure 5.4. For more information see this click ton the designation of local green space follow the link.

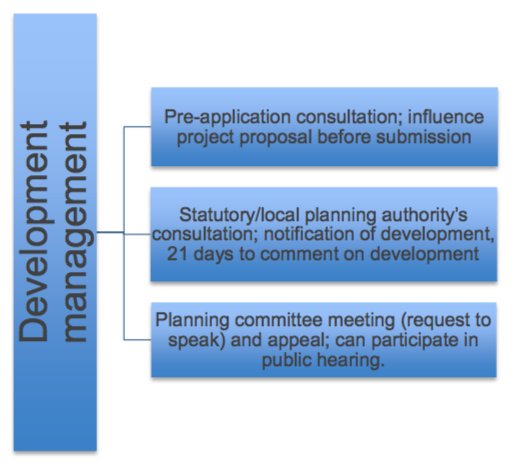

Outside policy area

A local community cannot only be active through the establishment of policies, they can also influence planning applications made by developers. The term ‘development management’ covers all the stages in such an application and local groups can influence the content of that application in various stages, see figure 5.3:

Developers need to consult with locals before finalising and submitting their proposals, which enables any local resident to contribute to the final form of any development proposal. After this proposal has been submitted the local authority of your borough is required to consult with you again, and you have 21 days to comment on the final development proposal. The final stage for participation takes place when the planning committee meets to discuss the proposed development and local groups can get involved after they have submitted a request to speak. Nevertheless, this last stage is often carried out by the planning inspectorate because local planning committee have denied planning permission, and the developer has appealed. The way to exert influence then is to write representations and speak at their hearings.

How to support involvement?

- Be pragmatic: suggest alternatives to the plans you are fighting

- Use data on green/environmental spaces to strengthen arguments (see GIGL)

-

(construct_arguments: ref regional plan; ref council policies; ref statutory bodies; value of green; mention material value) Review planning documents (if existent) on the case you are arguing for (see the website of your borough)

- Cite consultation reports from statutory bodies (see table 5.1)

- Relate comments on planning proposal to material considerations (see table 5.2 for examples)

[Table 5.1]

[Table 5.2]

[Table 5.3]

Other

Village Green:

To get registration as a village green, you will need to gather evidence that a significant number of local people have used the land without permission, without being stopped or seeing notices which stop them, and without being secretive about it, for a continuous period of 20 years. This works best where there is a woodland or open space which has been neglected by the owner for a couple of decades at some point in the last half century, and “colonised” by local people for recreational pursuits, which might be just dog walking.

Look online at the Open Spaces Society (http://www.oss.org.uk/ ), who has published an excellent book called Getting Greens Registered: A Guide to Law and Procedure for Town and Village Greens.

http://www.oss.org.uk/?s=getting+greens+registered

Also visit http://www.fieldsintrust.org/how_to_secure.aspx for lots more information on protecting outdoor recreational sites.

Register of Historic Parks and Gardens:

Inclusion of your park on this non-statutory register (maintained by Historic England formerly English Heritage) does not prevent development, but it makes it politically much more difficult for a local authority or the Secretary of State to support it.

Failing national registration, seek the inclusion of the park on the local list of historic parks and gardens or your local authority’s Sites and Monuments Record (SMR). Inclusion will give recognition to the site and help to resist inappropriate development.

For further information, visit http://www.historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/our-planning-services/

‘A satisfyingly furious response’

From the Crystal Palace Campaign, Philip Kolvin:

The developer at Crystal Palace applied for 14 pub licences. We employed a leading barrister to represent our case, and persuaded Mayor Ken Livingstone to appoint a barrister to co-object with us. We produced survey work to show how affected the area already was by licensing, not just residents but also businesses who complained of vandalism and intimidation.

We called politicians to show that they had never experienced such a level of opposition, and encouraged the leaders of many local groups to speak of the results of the opinion polls amongst their own members. Eventually, only one pub licence was granted, which wounded the scheme grievously. To make sure, we sent an “Alternative Prospectus” to the managing directors of the 100 leading pub and leisure companies, to explain to them how damaging it would be to their finances and PR to come to our park, and why, pointing to the stigma we had heaped on poor, beleaguered UCI. The response was satisfyingly furious. The scheme collapsed three months later.

Alternative relevant documents:

For further reference it is wise to look at other documents than this particular one as well, for example:

- Get the green space you want: How the Government can help – UK government regarding the 2011 Localism Act

- Open Space Strategies Best Practice Guidance – A Joint Consultation Draft by the Mayor of London and CABE Space 2008

6 Useful links

Organisations

Campaign for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE)

CPRE operate as a network with over 200 district groups, a branch in every county, a group in every region and a national office, making CPRE a powerful combination of effective local action and strong national campaigning.

www.cpre.org.uk

Community Development Foundation

The Community Development Foundation (CDF) Part of the Home Office, they develop and promote informal activity in local communities not unduly reached by the agencies concerned with more formal volunteering. www.cdf.org.uk

Directory of Social Change (DSC)

This organisation gives advice and support to voluntary organisations. The long-term vision is to be an internationally recognised, independent source of information and support to voluntary and community sectors worldwide. They help voluntary and community organisations to thrive through advice on: how to raise the money they need; how to manage their resources to maximum effect; how to influence the right people; what their rights and responsibilities are; and how to plan and develop for the future. The DSC also speaks out on issues affecting the sector through the media, public platforms and membership of government and advisory groups working for and within the sector.

www.dsc.org.uk

Environment Law Foundation

The Environmental Law Foundation (ELF) is the national UK charity linking communities and individuals to legal and technical expertise to prevent damage to the environment and to improve the quality for all. Through its network of members, ELF provides people with information and advice on how the law can help resolve environmental problems such as pollution, development and health.

www.elflaw.org

Federation of City Farms and Community Gardens (FCFCG)

FCFCG is the main national organisation involved with supporting community gardens and city farms across the city. They also have expansive knowledge and experience of allotments. If you have such a site, or are planning to start one, this organisation can offer you valuable advice and support.

www.farmgarden.org.uk

Fields in Trust

Protecting and improving playing fields is the core work of The Fields in Trust, formerly The National Playing Fields Association (NPFA). There is no statutory protection for our playing fields so the country’s irreplaceable recreational heritage is constantly at risk.

http://www.fieldsintrust.org/FIT.aspx

Friends of the Earth

Friends of the Earth is the largest international network of environmental groups in the world, represented in 68 countries and is one of the leading environmental pressure groups in the UK.

www.foe.co.uk

http://www.foe.co.uk/community/resource/how_to_guides

Groundwork

Groundwork is a federation of 50 trusts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, each working with their partners in poor areas to improve the quality of the local environment, the lives of local people and the success of local businesses. Groundwork works in certain areas of high deprivation across the UK. Its regional offices can be found on the main website.

www.groundwork.org.uk

Historic England

Historic England, formerly English Heritage works in partnership with central government departments, local authorities, voluntary bodies and the private sector to conserve and enhance the historic environment, broaden public access to the heritage and increase people’s understanding of the past. They are responsible for the maintenance of the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

http://www.historicengland.org.uk

Keep Britain Tidy

The campaign aims to achieve litter free and sustainable environments by working with community groups, local authorities, businesses and other partners.

http://www.keepbritaintidy.org/home/481

Local Government Ombudsman

The Local Government Ombudsmen investigate complaints of injustice arising from maladministration by local authorities and certain other bodies. There are three Local Government Ombudsmen in England and they each deal with complaints from different parts of the country. They investigate complaints about most local authority matters including housing, planning, education, social services, consumer protection, drainage and council tax.

www.lgo.org.uk

National Association of Cemetery Friends

The formation of a number of groups of volunteers with the common aim of conserving their local

cemeteries led, in 1986, to the founding of The National Federation of Cemetery Friends. Many of.

the Cemetery Friends started as pressure groups to counter owners’ neglect of a cemetery or proposals for inappropriate use. Often those who were successful continued their interest by monitoring the owner’s maintenance and restoration work and, if given the opportunity, helping in a practical way. http://www.cemeteryfriends.org.uk

National Federation of Parks and Green Spaces

The National Federation of Parks of Green Spaces (NFPGS) is a UK network of area-wide community Forums. It exists to promote, protect and improve the UK’s parks and green spaces by linking together all the friends and users Forums/networks throughout the country.

http://www.natfedparks.org.uk

Natural England

English Nature champions the conservation of wildlife, geology and wild places in England. They are a Government agency set up by the Environment Protection Act 1990 and are funded by the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/natural-england

Open Spaces Society

The Open Spaces Society protects common land and public rights of way. If you know of a blocked public path or encroachment on common land, or you want to register a ‘new’ green, they can help you, once you have joined the Society. This organisation can provide information on village greens and registration. www.oss.org.uk

Planning Portal

The main work of the Planning Inspectorate is the processing of planning and enforcement appeals and holding inquiries into local development plans. They also deal with a wide variety of other planning related casework including listed building consent appeals, advertisement appeals, and reporting on planning applications. www.planning-inspectorate.gov.uk

Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI)

The RTPI influences the development of planning policy at regional, national, European and international level. www.rtpi.org.uk

Save Britain’s Heritage

Through press releases, lightening leaflets, reports, books and exhibitions, SAVE has championed the cause of decaying country houses, redundant churches and chapels, disused mills and warehouses, blighted streets and neighbourhoods, cottages and town halls, railway stations, hospitals, military buildings and asylums. www.savebritainsheritage.org

The Conservation Volunteers

TCV is the UK’s largest practical conservation charity. Founded in 1959, they have helped over

130,000 volunteers take hands-on action to improve the rural and urban environment. TCV is a national organisation with local offices around the country.

http://www.tcv.org.uk/

The Victorian Society

The Victorian Society is the national society responsible for the study and protection of Victorian and Edwardian architecture and other arts. It was founded in 1958 to fight the then widespread ignorance of nineteenth and early twentieth century architecture.

www.victorian-society.org.uk

Town and Country Planning Association

The purpose of the Association is to promote and improve the art and science of town and country planning and to promote, encourage and assist in all other arts and sciences connected therewith. The TCPA is working to improve the quality of people’s lives and the environments in which they live.

www.tcpa.org.uk

Wildlife Trusts

The Wildlife Trusts partnership is the UK’s leading conservation charity exclusively dedicated to wildlife. The network of 47 local Wildlife Trusts and the junior branch (Wildlife Watch) work together to protect wildlife in towns and the countryside. They care for over 2,400 nature reserves from rugged coastline to urban wildlife havens. With more than 382,000 members, and unparalleled grass roots expertise, The Wildlife Trusts lobby for better protection of the UK’s natural heritage and are dedicated to protecting wildlife for the future. www.wildlifetrust.org.uk

Examples of Campaign Websites

http://savetrentpark.org.uk/ http://friendsofkingeddies.blogspot.co.uk/ http://lordshiprec.org.uk/bwflordship/ http://www.crystalpalacecampaign.orghttp://ourtottenham.org.uk

http://www.theheswallsociety.org.uk

http://www.greaterlondonnationalpark.org.uk

http://www.saveherveyroadsportsfield.co.uk

http://www.protectdundonaldrec.org

Examples of Petitions

https://you.38degrees.org.uk/petitions/save-ermine-road-and-plevna-crescent-open-spaces-in-tottenham https://you.38degrees.org.uk/petitions/stamford-protect-our-green-space